A Slow Monday

I began the day today with a slow start. On Mondays I like to ease into things with a walk through the forest (a luxury, I know!) -a way to loosen the mind for the tasks awaiting me: putting together a presentation, preparing a lecture, writing my book, or working on my PhD research. There is always more than enough to do, which is why it feels important to get moving, both literally and figuratively.

This morning, though, that walk didn’t happen. I had to wait for the carpenter finishing the attic. Hardly a tragedy, but it knocked my rhythm off balance. Before I knew it, I was sitting in the chair by the garden window, phone in hand, tears in my eyes. Scrolling without thinking, I stumbled across alarming news updates, the weight of which still sits heavy in my stomach.

I won’t go into specifics- you can probably guess the tenor of what I mean. The state of the world isn’t encouraging. Human rights trampled daily. America launching a mindbaffeling Gestapo-like campaign that pays citizens $50,000 to report their neighbors to ICE. The atrocities in Gaza rolling on unchecked. Antifa declared a criminal organization. And when far-right extremists torch The Hague, we neatly rebrand them as “hooligans.”

But Monday presses on. Work awaits. Work I enjoy. And the truth is: I can stop scrolling. I can swallow hard, make myself a coffee, and begin again. How many people cannot?

Wonder

Yesterday my colleague Kevin and I spoke at Fraterhuis Zwolle about film and wonder- about how wonder, astonishment, and revulsion are different shades of the same emotional palette. Plato once claimed that it is not doubt, but wonder that lies at the root of all knowledge. Hannah Arendt echoed him, writing that wonder - not skepticism -is the true source of thought.

Wonder arises when we suddenly notice that something is rather than nothing. It is pausing, attending, perceiving: you see that the sky is blue, and you marvel at it, asking yourself why. The philosopher follows this wonder wherever it leads, asking questions about being itself, about the origins of all things.

And sometimes wonder tips into astonishment. Astonishment, you might say, is framed by the culture you grew up in, your temperament, the lenses through which you form judgments. To look at something with astonishment implies distance, a kind of evaluative stance. Yesterday someone remarked, quite rightly, that astonishment sometimes comes before wonder. I wonder if that is true, or whether the judgment had already been made unconsciously.

Revulsion, then, marks a moral line crossed: a situation where there is no space left for wonder, perhaps a flicker of astonishment, but which demands involvement from the witness. For Arendt, wonder was never a purely intellectual exercise. It was an everyday mode of being engaged with the world.

The Zone of Interest: Revulsion

We show a clip from The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer, 2023), a film that portrays the domestic life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss. In a key scene, his wife Hedwig strolls through the garden as she entertains her mother. They talk about flowers, plants, honey made by the bees. Her mother calls her the “Queen of Auschwitz,” and Hedwig laughs. Behind them, the low hum of the ovens. A dog barking. Dull bangs. Shouts.

The camera lingers at the end of the scene on close-ups of the blossoms in the garden, petals, colors, light. But behind this beauty the shouting rises, gunfire cracks, and then: almost silence.

When the lights come back up, I always watch the faces of the audience, hear the held breath in the room. We let a few seconds pass in silence before speaking. Then we ask them- not what we thought, but how they experienced it. What did that conversation sound like to them? What did the close-ups of flowers do?

The most common reply: the flowers’ beauty no longer mattered. Yes, they saw it. They saw the artistry of the close-up, the richness of the colors. But that beauty was hollowed out, made unreachable by the soundtrack and by the knowledge of what was happening just beyond the frame.

The scene still leaves a stone lodged in my stomach.

These three, wonder, astonishment, revulsion- are emotional and moral responses to what we witness. And because we all know them, we are, in our essence, engaged inhabitants of this earth. We marvel, we express astonishment, we recoil. We form judgments. And we ask (at least we should), why.

At the Table

In two weeks, I’ll be a table guest at EICAS in Deventer, in conversation with geoscientist Daan den Hartog Jager, Annegret Kellner, and Sibylle Eimermacher. Kellner and Eimermacher have made extraordinary works for the Land-to-Land exhibition, reflecting on our relationship with plants and minerals. Their work is inspired in part by James Lovelock, whose Gaia hypothesis proposed that even a single organism can influence an entire ecosystem. The idea that Earth regulates itself as a living system shows how everything is entangled with everything else: the smallest gesture, the tiniest being, may ripple through the whole.

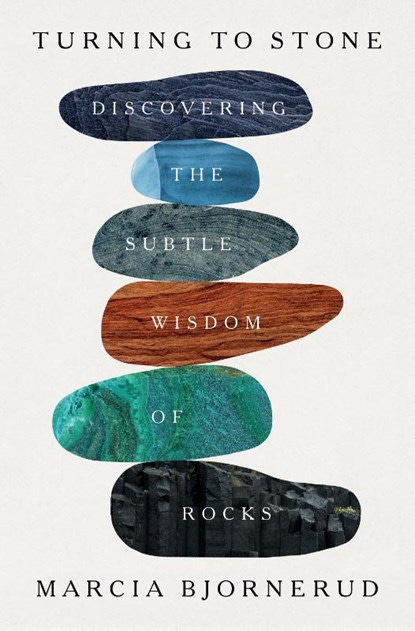

I look forward to that discussion. I’m particularly curious about Hartog Jager’s ideas. Recently I read (and listened to) Marcia Bjornerud’s Turning to Stone: Discovering the Subtle Wisdom of Rocks. It is not a dry geological manual, but a woven story - personal and planetary. Each chapter centers on a stone: sandstone as a marker of youth, basalt as a regulator of climate, other rocks that both carry and anchor her life. Bjornerud shows that rocks are not mute witnesses but active infrastructures: sandstone aquifers purify our drinking water, basalt shapes the atmosphere. Her book reads as an invitation to see Earth as a living system, and to rediscover our entanglement with it.

Searching for Ground

To be honest, this Monday morning, I was searching for ground to stand on - something to hold during my preparations for the EICAS conversation. I write and think often about our place in the universe in relation to the Earth. And yet scrolling my phone this morning, then turning to lecture notes, I lost all sense of urgency. What does it matter? Why should staring into the distance matter at all to who we are?

And yet, as I began writing about the astonishment and revulsion I felt this morning, something shifted. Slowly, drop by drop, I realized: it is precisely in asking about the necessity of such conversations, in the face of horror, that space reopens for wonder, astonishment, revulsion.

Perhaps that is the movement I need to practice again and again: from the suffocatingly near to the breathtakingly far. From the headlines on my phone to the moon overhead. One steals the air from my lungs; the other gives me space.

The Universe as Political Arena

For me, studying and thinking about the universe is both remedy and political act. A telescope may point outward, but in truth it sharpens our inward gaze.

To look at the stars is to invert the ordinary. The unusual becomes familiar; the familiar strange. Staring at the Milky Way, reading of black holes, peering at the moon through binoculars - it satisfies something deep. Everything here seems so small, so trivial against that immensity. And yet we sense ourselves to be part of it: part of the spheres, the devouring holes, the wandering rocks. The thought makes me chuckle often: nothing matters, therefore everything does. I give weight to things because I care. We all do, when we pay attention. And it begins, always, with wonder.

Politics runs through science, even astronomy. NASA is being stripped down. The Science Mission Directorate, responsible for the bulk of NASA’s research, may see its budget halved. At the same time, language that makes room for imagination and diversity is being erased. On January 22, 2025, NASA HQ ordered staff to remove all references to diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility; to women; to leadership by people of color - from all public websites. Even the Artemis promise, that the first woman, the first person of color, the first international partner would walk on the Moon - has quietly vanished.

The regime doesn’t just dismantle budgets and knowledge systems; it erodes the credibility of science itself. The consequences will ripple far beyond what we can imagine. It is about which stories our children will, or will not, hear. Which futures they will, or will not, be able to imagine. When a narrow elite controls the story, when diversity is excluded, then that is the only future left to us. This is true in politics, in culture, and also in science, even in the study of space. I talked about this during a lecture earlier.

What antidote is there? To step outside your own frame: go to the theater, to museums, to voices whispering alternatives. Don’t let the algorithm dictate your world. Say yes to the rave, to the sleep-concert in the castle garden. Walk with a toddler (children live in perpetual wonder). Read authors you do not know.I repeat this at every opportunity: broaden your interests, deepen them. It is not easy, it takes effort, for me as well. But curiosity, diversity of perspective- these are the roots that hold us steady when the wind blows from only one direction.

How we look outward is how we look inward. The urge to study the stars has never been about the stars alone -it is always, also, about ourselves. Religious, scientific, humanist motives all share the same hope: that by learning what is out there, we might better understand what is in here.

And besides, there is no outside and inside. We are all part of the larger whole. Some call it god, some conviction, some description, equally valuable, so long as it is not imposed. My conclusion remains: we are part of everything, and everything part of us. Our microbiome proves as much: billions of microbes, more numerous than human cells, inhabit us. They digest for us, protect us, shape our moods and thoughts. We are never alone; we are interwoven.

And the simplest, most humbling truth: we are stardust. The oxygen, iron, calcium, carbon in our bodies was forged in the hearts of stars that exploded billions of years ago. Their death was our beginning. We are not apart from the universe; we are the universe.

These thoughts are sobering, but also consoling.

Wonder is about giving something your attention. For me, space, the stars, and the writing and thinking around space exploration are my weapon of choice. But I can easily imagine other ways of arriving at the same sense of perspective, connection, and wonder. For one person it may be music, for another travel, or simply a conversation at the kitchen table.

Wonder, astonishment, and revulsion are not escapes from reality, not a form of escapism, but ways of inhabiting it. Ways of staying engaged. Ways of preserving our humanity. They are about not letting things slip away into silence, but holding on, facing them, sharing them.

Yes… I think I managed, today.

Sabine - I love how you think about and write about wonder.

Have I ever mentioned to you the book American Technological Sublime by David E. Nye? An excerpt from it’s description on Amazon:

“What has filled the American public with wonder, awe, even terror? David Nye selects the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, the eruption of Mt. St. Helens, the Erie Canal, the first transcontinental railroad, Eads Bridge, Brooklyn Bridge, the major international expositions, the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909, the Empire State Building, and Boulder Dam. He then looks at the atom bomb tests and the Apollo mission as examples of the increasing ambivalence of the technological sublime in the postwar world.”

Worth a look if you have interest.